New Historical Find Reveals Much about Liberia’s Early Beginnings

Plan of the town of Monrovia.

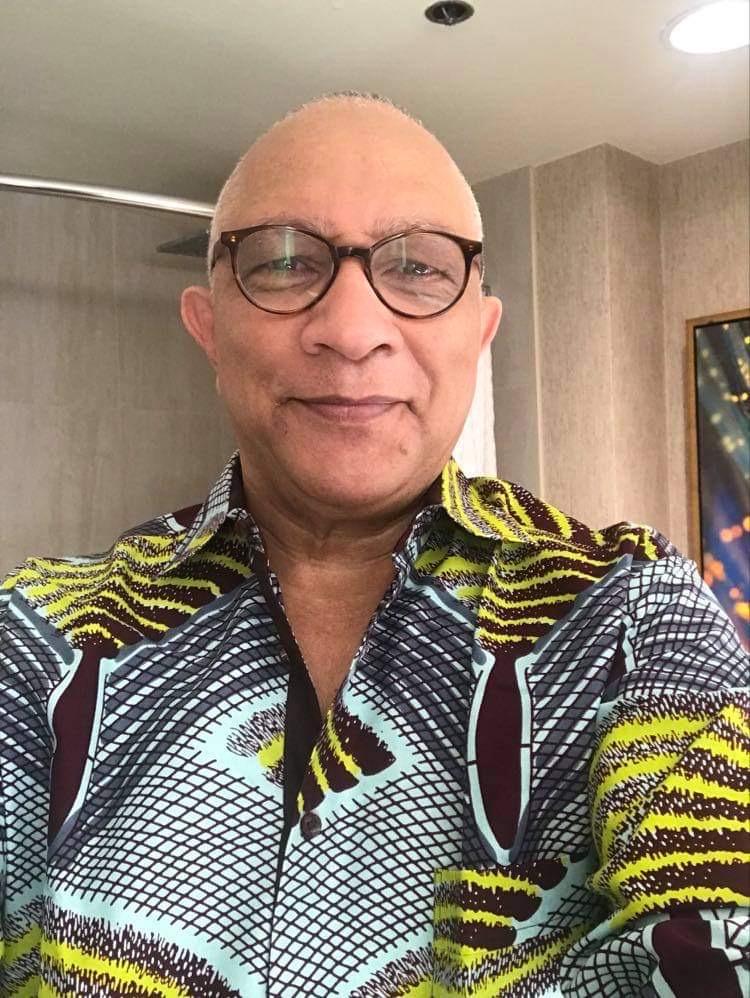

It may seem like just another piece of paper at first, but not to a career historian like Dr. C. Patrick Burrowes, who has been scouring the globe for artifacts, documents, testimonials, and remnants of any clues to the puzzle called Liberia. His recent discovery of the original land purchase agreement for Cape Mesurado, between members of the American Colonization Society and the ethnic groups they met here, provides clearer understanding about the nature of the natives and how they related to the earliest repatriates before the founding of the Republic of Liberia.

At a point in time when Liberia is poised to celebrate the bicentennial of the first group of repatriates form the United States of America, the discovery by Burrowes appears to both establish a new perspective from which the nation’s history could be told, and help clarify and correct long-held beliefs that may have fueled division among peoples for more than a century.

In this exclusive interview with the Daily Observer, Dr. Burrowes discusses his groundbreaking discovery and what it could mean for the country now and perhaps for the next 100 years.

C. Patrick Burrowes, Ph. D. is Liberia’s leading historian. Among other academic positions, he served as the Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Professor at Marshall University. Burrowes is the author of Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea: A History of the Liberian People Before 1800, as well as several other books. His research has received awards from several organizations of international scholars. Patrick holds a Ph. D. from Temple University. Young Liberians call him “the people’s professor” because of his willingness to share his knowledge of Liberian history.

Questions are in bold.

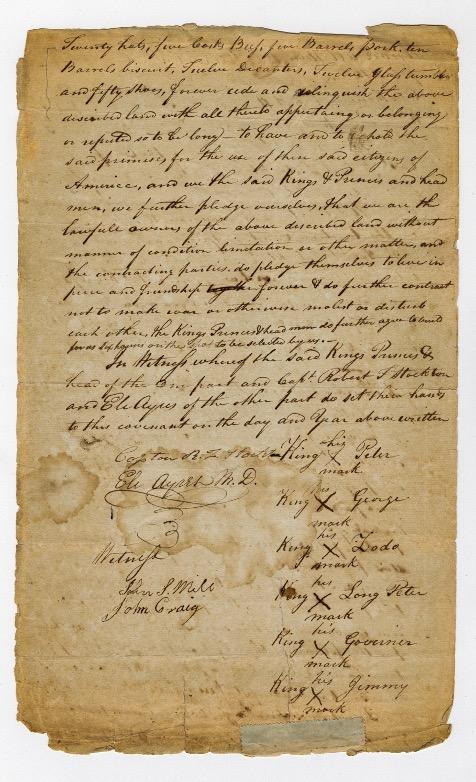

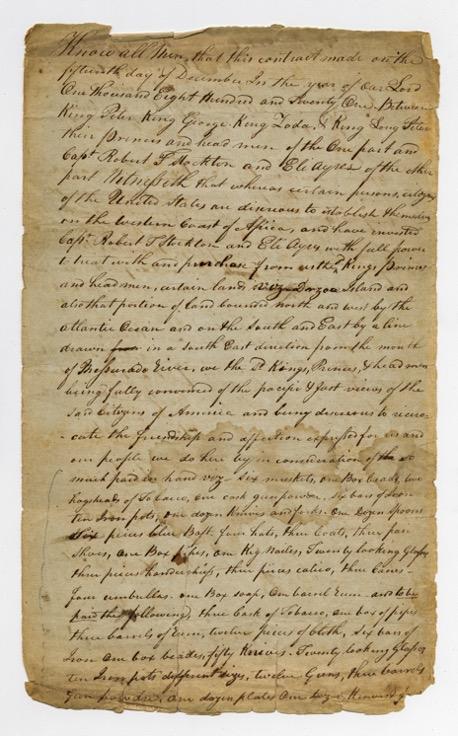

The original purchase agreement for Cape Mesurado was signed by six local rulers as well as an agent of the U. S. government and a representative of the American Colonization Society (ACS). It had been missing for almost 200 years. How did you find it?

The document has been missing from the ACS papers in Washington, DC, since the 1830s. I found it among some papers of Elias B. Caldwell, which are housed at the Chicago History Museum. Caldwell worked on a part-time basis as secretary of the ACS, but he was the full-time clerk of U. S. Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington. Caldwell apparently had some ACS papers at the Supreme Court when he died in 1825. Those documents were transferred to Chicago in a collection of Justice Washington’s belongings. Knowing that Caldwell had died while serving as secretary, I went looking for this purchase agreement among his papers. That search led me to the Chicago Museum.

In your view, what stopped other people before you from finding this important document?

I have spent a lifetime researching Liberian history. As a result, I have come to know the ACS and the people who worked for it very well. As a historian, studying a group of people well helps you to understand how they thought and behaved.

Any document could be a forgery. How do you know this one is the original?

First of all, the document is in the handwriting of Eli Ayres, the American who signed it on behalf of the ACS. Second, the paper is aged, not modern. Third, its location inspires further confidence in its authenticity. After all, both Caldwell and Washington were officers of the ACS, which was the original keeper of the document.

What were the appropriate titles of these rulers – “kings” or “chiefs”?

Neither. The men who signed the land purchase agreement bore titles like Tawy in Dei or Worloba in Bassa, both of which translate to “great man.” Clan leaders, who often served as town administrators, were called Ba in both Bassa and Dei. When Europeans first came to Africa, they often referred to local rulers as “kings.” But that was inaccurate because many rulers in the area now known as Liberia did not transmit power from father to son. They also did not rule over millions of people, like European monarch did. Later on, Westerners switched to using the term “chief.” But that label is racist because it is only applied to African and Native American rulers, not Europeans, Arabs or Asians. It is also imprecise because it is used both for some rulers in Nigeria who govern over millions as well as for others with a few thousand persons in their domains.

Were the six local rulers equal in power?

A5. No. The most important personage among them was Tawy Peter; he belonged to the land-owner family among the Dei, and the Dei were the first to settle in the Cape Mesurado area. His assistant was Ba Bey (also known as Long Peter). Ba Bey was responsible for representing Peter to outsiders, similar to a foreign minister. At the other end of the power spectrum from Tawy Peter was Gwogro (or George), who governed a Mamba Bassa town at the foot of Cape Mesurado with less than 20 houses.

There is a bridge from Bushrod Island named for Zolu Doma. Was he one of the local rulers who signed the purchase agreement?

No. Those who named the bridge apparently confused Zolu Doma (also known as Peter Softly) with Peter, who signed the agreement. In truth, Zolu Doma lived nowhere near Bushrod Island; he was in Cape Mount. These kinds of embarrassing mistakes happen because Liberian policy makers do not respect historians, unlike their Ghanaian counterparts whose highly successful Year of Return relied heavily on the expertise of their best historians.

The local rulers who signed the purchase agreement all had English names. Did the Americans give them those names?

No, the Americans did not give them those names. By the late 1600s, there were individuals living at the mouth of the Junk River who spoke Dutch and Portuguese; there were French and Portuguese speakers near Grand Cess. Writing about the people of River Cess, one French writer said it was customary by 1667 for persons of note to take a European name. Another European visitor noted that children along the coast of what is now Liberia were usually given Western names in “grateful remembrance” of any kindness done to their parents by whites.

According to E-L-They-Say, Captain Robert F. Stockton forced the local rulers to sell the land “at gunpoint.” Is that true?

No. This myth had some appearance of credibility: Captain Stockton, a veteran of several duels, was no stranger to gun play. And he did brandish a pistol during the negotiations. Stockton pulled his gun in response to two pro-slavery outsiders who had come from Freetown seeking to sabotage the negotiations. At that moment, the Americans were far outnumbered by local forces who were armed with 60 or more muskets. In addition, the purchase agreement was signed a full day after Stockton drew his pistol, so the local rulers had more than enough time to change their minds. In truth, E-L-They-Say sensationalized Stockton’s actions and stripped them of context.

Among the indigenous people of the area now known as Liberia, was it possible for strangers to acquire land?

Yes. An individual stranger could get access to land in a community by providing gifts to the land-owning family, which was usually the first to cultivate the land. Typically, a group of strangers could not buy cultivated land that was occupied. It was much easier for stranger groups to gain access to uncultivated land by providing gifts to the landholders. That is how the Vai first and then the Gola later came to settle among the Dei in Cape Mount.

Some people say the purchase agreement was invalid because the local rulers did not understand Western contracts or the idea of selling land. Is that true?

A10. No. From 1807 to 1820, several Europeans occupied land near Cape Mesurado, with the acquiesce of the local rulers. In chronological order, they were Mr. Jump, Joseph Denison, Mr. Smalley, Bostock and McQuinn, and Mr. Hayes. Most if not all of them were involved in the African slave trade. In short, local rulers understood Western contracts because they had been involved in business arrangements with Westerners, including pre-purchase agreements, for centuries.

How could the rulers understand the contract if local people did not speak English?

That’s not true. A biracial trader named John Mill served as scribe and interpreter for the local rulers during negotiations for the land. He was educated in Liverpool, England, for about ten years. Mill was the owner of Providence Island, which he sold separately to the Americans. In addition to Mill, many local people spoke English because British traders and the British navy were very active in West Africa. Kru men were working aboard every ship in the British Antislavery Squadron, where they learned some English to communicate with their commanders and other crew members. Sao Boso, the ruler of the Condo Confederation centered around Bopolu, spoke English. He acquired the nickname “Boatswain from working for years aboard a British ship.

By relying on written records, you risk telling a one-sided story from the point-of-view of the U. S. government and the American Colonization Society. What have you done to ensure that our ancestors’ side of the story is included?

I used oral histories and artifacts dated by archeologists to determine that the Dei were the first group to settle in the region. According to oral traditions, a Dei woman named Wholo facilitated the negotiations and provided canoes and palm thatch to the repatriates so they could build their first shelters on Providence Island. I also consulted books written by European visitors to Cape Mesurado dating from 1507 to 1821. Before writing about this purchase agreement, I spent 35 years researching and writing a book on the history of the Liberian people before 1800 that is over 400 pages long. To write that history, I used oral histories, archeological findings and studies of African languages, as well as books translated from Arabic, Portuguese, French and Dutch. My book, which is called Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea, is the only scholarly book on that period.

How much land was transferred in 1821? Some people say it was over one million acres.

A13. Those claims are based on pure speculation. I used a map of Monrovia, drawn in 1824, to calculate the actual dimensions of the land purchased by Stockton and Ayres. It was about 140 acres of rocky, uncultivated land. Most of what is now the city of Monrovia was acquired later, including Bushrod Island, Caldwell, etc.

How much did the Americans pay for the rocky land at the top of Cape Mesurado?

They bought it with $300 worth of weapons, rum and other merchandise. Those would be $7,000 in today’s dollars.

Was that a fair price?

At that time, an equivalent tract of land in the U. S. would have cost $175 or $4300 in today’s dollars.

Why did the local rulers sell land to the Americans? What was their primarily motivation?

At the time, the biggest international conflict was between those involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade and those who wanted to abolition it. Many Liberians today assume that opposition to the slave trade was limited to people living in Western countries, but that was not the case. There were Africans who opposed the kidnapping and selling of their fellow Africans from day one. In selling the land to abolitionists, the local rulers cast their lot with the forces of abolition. After listening to two pro-slavery Africans who came from Freetown to try and block the land sale, they ultimately sided with the Americans who wanted to end the selling of African captives. Mill had been involved in the lucrative slave trade but had given it up in 1820 due to a troubled conscience. One can say that Liberia was founded as an abolitionist nation, a vision that was supported both by those who sold the land at Cape Mesurado and those who came to live on it. The rulers strategic calculation was correct because abolition ultimately prevailed.

Some people say the local rulers changed their minds after selling the land. Is that true?

No. Between 1825 and 1828, the nascent Liberian colony expanded through four additional land purchases. Three of those purchases involved land sold by the same local rulers who signed the original contract.

How do you refer to those who came from America to live in Liberia? Some call them Americo-Liberians and ex-slaves.

I call them repatriates. That word literally means “people who return to the land of their ancestors.” Words like “Americo-Liberians” and “ex-slaves” are used to portray them as alien. To label people whose families have lived here for six generations as “Americo-Liberians” is similar to calling all Malinke-speakers “Malian-Liberians.” In addition, “ex-slaves” is deliberately used by some foreigners and some politicians as an insult. It is just as wrong as calling Dan people “Gio” (which means slaves). The use of such language fuels genocidal thinking and behaviors, so it needs to be stopped as it was in Germany after World War II and in Rwanda recently.

Everybody says the repatriates were very different from the people they met on the ground. Was that true?

That is patently false. Their foods were similar. Black people in America like people on the coast of Liberia ate greens, meats, seafood and rice, seasoned with smoked herring and salt pork. Back then, black women in America wore head-ties and plated their hair. Even today, African culture is alive in Brazil, the Caribbean and the Southern United States. Imagine how much more culturally connected the Diaspora was to Africa in 1821. Those who came to live in Liberia from the U. S. were not citizens of America. For that reason, they did not call themselves Americans or think of themselves as Americans. Men like Lott Cary, Joseph Jenkins Roberts and Hilary Teage, for example, all called themselves Africans. Due to racism in America, black Christians founded their own denomination which they called the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

When you were doing research on the purchase of Cape Mesurado, what surprised you the most?

What surprised me the most was the presence of several very powerful women. There was Wholo, the Dei woman who facilitated the negotiations and provided canoes and palm thatch to the repatriates so they could build their first shelters on Providence Island. According to oral traditions, there was a level or degree in the Dei branch of the Sande Society that was named after her. Another woman named Phillipa live on Bali Island with hundreds of dependents, one of whom, Ba Caia, succeeded her. Had Phillipa not died shortly before Ayres and Stockton arrived, she probably would have participated in the negotiations for land. Another woman, Mary McKenzie, sold her portion of Bushrod Island to Liberia in 1827, without any male support or opposition. A biracial woman from Cape Mesurado was the concubine of the British governor in Freetown.

What is your advice to Liberians who are interested in history, especially young people? A21. I have two recommendations. First, take our history very seriously. That means reading alone or with others, even if you don’t like reading. Without accurate knowledge of the past, we will never advance. Second, stop accepting uncritically the lies you were told by your uncoos. Many of them sought to delegalize Liberia by distorting its history. No country on earth has a flawless history. None. But we, Liberians, forever flog our ancestors for their shortcomings while worshipping the flawed histories of others. Younger generations are now reaping the bitter fruits sown by their elders in the field of history.